Trust the Process, Part 2: Portfolio Rebalancing

In October 2017, we shared our process for when a client requests a cash distribution from their accounts. In this second post of the “Trust the Process” series, we’ll talk about the steps and decisions that go into portfolio rebalancing.

At its core, the concept of rebalancing is simple. Start with a target percentage allocation of each asset in a portfolio, and as asset values change, periodically make trades so that the portfolio doesn’t drift too far from those targets. Essentially, you’re selling portions of assets that have gone up in value and using the proceeds to buy assets that have either stayed the same or have decreased in value. Rebalancing is a great tool to reduce portfolio volatility and, depending on the nature of the underlying assets, can even lead to increased returns.

In practice, things get more complicated. Investors must establish a rebalancing philosophy by answering some important questions, such as:

- How frequently should one rebalance?

- Should an investor always rebalance back to their target weights, no matter how much or how little deviation there is from a target?

- Should rebalancing happen at the account level or across all an investors’ accounts (i.e., at the “household” level)?

- How should an investor think about taxes, since at some point he or she may have to sell something in an after-tax account that’s worth more than its cost?

These are the sorts of questions that generate content for doctoral dissertations and academic journals. Based on our review of that research, Woodward Financial Advisors has settled on a philosophy that can be summed up as, “Check often, but trade infrequently.”

To start, we construct portfolios at the household level. That allows us to put less tax-efficient asset classes (like taxable bonds and real estate mutual funds) in tax deferred accounts, so that clients don’t have to pay taxes on any interest generated throughout the year. We call that “asset location.”

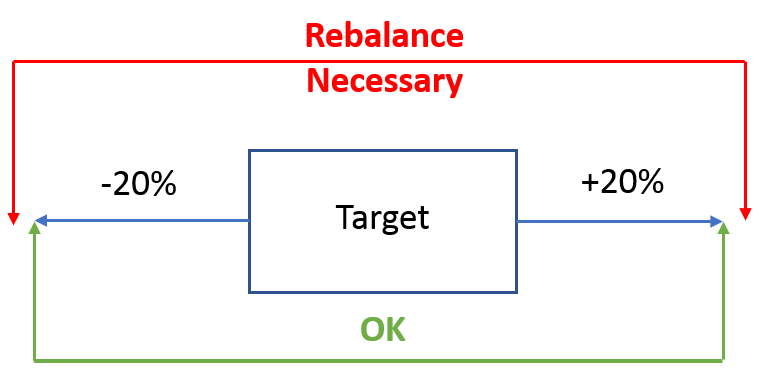

Next, we establish target weights for each asset class. But rather than blindly rebalancing back to these target weights at every review, we establish “tolerance bands” of 20% around each target. Think of those bands as “guard rails.”

For example, if we thought that Asset Class A should make up 10% of a portfolio, we’d be ok if that asset class made up anywhere between 8% and 12%. But if it strayed above 12%, that would be our signal to sell a portion. These bands help reduce the total transactions and associated costs when rebalancing.

If we need to make trades in taxable accounts, we do so with an eye on taxes. We’ll check to see if there are investment lots that we can sell at a loss or, barring that, at a reduced gain. We may also sell other asset classes that might not need rebalancing if they can be sold at a loss to offset gains, provided we can do so without selling so much that we violate the tolerance bands. And due to our “household” approach to portfolio construction, we may sell an asset class in one account but buy it back in another, so that we keep the whole portfolio in balance when all the transactions are done.

We review portfolios multiple times throughout the year for rebalancing purposes, in addition to using the tolerance bands as our guides whenever clients request cash or add cash to their portfolio. Since some of the asset classes we use can be volatile on their own, these multiple checks help us catch when some of those asset classes go outside of their bands. If we only rebalanced once or twice per year, we’d miss those opportunities.

Our rules-based, disciplined approach prevents emotion from guiding our actions. And the documentation of and adherence to the steps in the process result in a consistent client experience.